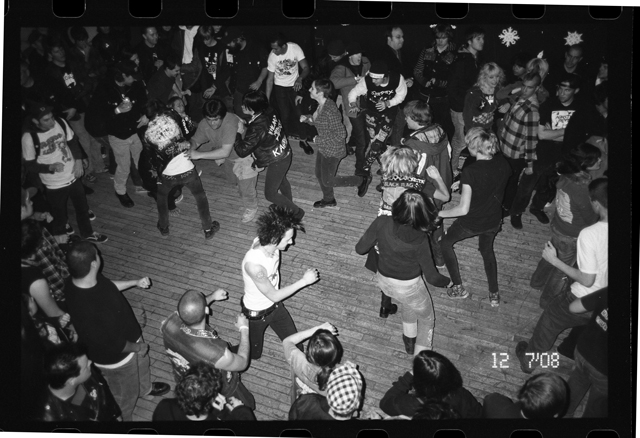

I meet Italian-born photographer Alessandro Simonetti at Everyday Coffee on Johnston Street, Collingwood. We’re here to talk about his show Never Forget The Warriors, a photographic exploration of the reunion of A7 – New York’s notorious punk and hardcore club. The series was shot over the course of one night in 2008 at another NYC venue, The Knitting Club, where for an evening middle-aged punks reunited and mingled with audience members who were too young to order a beer at the bar. Simonetti grew up surrounded by subcultures like punk, skinhead, and graffiti, so our location today seems fitting. Further up the street from where we’re sitting is the Birmingham Hotel, for a long time Melbourne’s spiritual home of skinhead culture. A few metres in the opposite direction are The Tote, and the famed Keith Haring mural that adorns Collingwood Technical College – important cultural touchstones for the punk and graffiti communities respectively.

Of course, times have changed. Elements of the Haring wall have been repainted by a well-intentioned council, The Tote has narrowly avoided permanent closure a couple of times, and these days The Birmy is more flatscreens and footy than boots and braces. As every subsequent generation makes the transition from one-eyed teenage fanaticism into the reality of adult life, there’s an enduring sense that things were better, simpler, more authentic than they appear to be now. That misplaced nostalgia forms the basis of much pop-cultural discourse, but it’s also inherently a falsehood. New generations re-interpret, recycle, and re-invigorate older traditions – bringing new life and form to the memories and practices of those who precede them. Over an espresso on sunny Johnston Street, Simonetti explains this cultural dichotomy and the way his work relates to it.

So you grew up in the Italian punk scene?

I grew up listening to punk, straight-edge hardcore, and hip-hop. My hometown where I grew up is called Bassano del Grappa – about 50,000 people live there.

How were there manifestations of punk and hip-hop in a town of 50,000 people in Italy?

Historically Bassano del Grappa is rich in art, rich in design, and a lot of fashion brands are based there. They’ve always been receptive to an interesting movement, you know? But when I used to live there, growing up in the early ‘90s the internet wasn’t around. Looking back, it’s interesting how these kids found stuff.

Was it US based stuff that was finding its way to you, or was it an Italian take on that culture?

Italy, especially my generation, grew up with the myth of America. All the good shit was coming from America, even (ex-Prime Minister) Berlusconi basically based all of his TV communication on American shows. Getting into graffiti in the first place linked me with New York City in particular. But at that point these were all subcultures. Hip-hop concerts, reggae, oi, skinhead, they were all gravitating around this scene of squats. In my hometown was a little squat, really extremely politically left, like straight communist. It was the only place you could get access to that kind of stuff. In that place I saw VHS projected screenings of Wildstyle and Style Wars for the first time, and I saw my first local and international punk bands.

Do you think having less access to those cultures as a whole made you more receptive to picking up on elements from different youth movements? You seemed to be across all of them.

Yeah, that’s the thing. My friends and I were like a group of 10 or 15 people including skaters, punks, dudes with dreadlocks – so it really was an exchange of culture. For me going to a hip-hop concert or going to a punk concert was equally cool. But I think it was more a generational thing. Punk and hip-hop are not necessarily two realities that you can combine together.

So you moved to New York six years ago, is that right?

Six or seven years ago. I arrived there just attracted by graffiti and music. When I moved there I wasn’t even speaking English, because the Italian school system sucks. They never let me study English, and at that point I wasn’t going to go to another school after class to learn English. After school we kids were out on the street, all painting and stuff. In a way I closed a cultural circle by moving to New York.

Were you following those same cultures when you got there?

More or less, in a sporadic way. When I arrived in New York I stopped painting graffiti, you get more into the hustle. You grow and your taste expands. When you’re a teenager, you’re narrow minded – you don’t look at other influences. Now and then I got to a concert, but it’s not like when I was kid when it was every other day.

You live and die for it when you’re a teenager. With the series that you’re showing here there’s obviously a sense of nostalgia that is present at any kind of reunion show. Did it feel like that for you?

For me it was a continued déjà vu. The Italian punk scene was so raw because it wasn’t happening in the clubs, like in New York. It was happening in squats, it was more extreme. Fights between skinheads and punks, all kinds of drugs, underage kids smoking and drinking. So when I went [to the Knitting Club show] in 2008 and there are all these 17-year-old kids… it was interesting. In America they are very strict about drinking. So you’re seeing these kids with all the patches, and all the fucking studs and mohawks, but they’re drinking juice. On the other side, backstage, you have 50 – 60 year old singers and musicians. It was really interesting, and sometimes grotesque too.

Is it strange seeing kids that couldn’t be there the first time round? There seems to be a fascination with recycling culture, is that a good thing?

Well I don’t think it’s a bad thing. I lived in a certain kind of time, and that’s what happened. I fully got into the graffiti and music scene. I understand that a kid who grows up now has all the tools to learn in a week what we did in two decades. It’s not necessarily a negative thing, just a matter of adjusting to the times. Sometimes I think about when we were kids, and how we got in touch with this stuff. Because when I was 16, we didn’t have any international bookshops or stores. Even if you wanted to get a certain kind of shoes because you were into hip-hop and you want to wear Puma, you have to take a train for two hours and find this spot that people told you about because you didn’t have google maps to find it. In a way, I’m glad I had that experience because it was more of a commitment. Now I feel like it’s more a matter of embracing an aesthetic than it is about a culture.

Was the title Never Forget The Warriors taken from the Blitz song ‘Warriors’?

It was taken from the Blitz song that later got covered by Judge. The reason that I know that song really well is because of this really popular straight edge hardcore band from my area of Italy, called The Last Man Standing. At some point at every show they’d play a cover of ‘Warriors’. I remember it was the only [English] song that I knew well, or at least the chorus. At that point only one in ten of my friends knew English, so we knew the sounds but we didn’t know what the fuck we were saying. But ‘Warriors’ was a very simple chorus, and it was a really powerful song as well. When I put together this project I wanted to find a title that held that sense of reunion and that nostalgic feeling, so Never Forget The Warriors was in a way what these kids were doing.

You self published the series originally as a book, was that a nod to the DIY elements of those cultures?

In a way it is, when I work on publications there’s a clear link to those DIY roots. For my generation and the generation after, print matter wasn’t an aesthetic choice – it was the only choice. I remember working on graffiti zines, vegetarian anti-corporate zines, animal liberation publications, so that kind of printing and aesthetic is a natural thing for me. Printing art books like this is a renaissance for me.

We touched on this before, but do you think that having that much digital access to information and imagery means that some of that artistry is lost?

Definitely, it’s a different way to digest content. For myself when I spend a lot of time on the internet, I get overwhelmed by images. In a way it’s led me to consider the subjects that I shoot and try and go deeper with what I’m doing. Now that images are so accessible, sometimes I feel like they lack depth. But again, I don’t neccesarily see it as a bad thing. It’s just something where you’ve got to adjust the way that you communicate using that media. It’s always sad when you hear old photographers say “digital killed photography,” it didn’t kill it – it just changed it. I imagine a portrait painter in the 1800s seeing this guy working with a new machine that takes images being like “What the fuck? This isn’t art, it’s a science.” It’s the same thing, it’s a change of behavior and mediums.

Do you think that because there’s such a high turnover of information that those subcultures you grew up with can exist in the same forms that they did a few decades ago?

I don’t think so, I think that is pretty much done. Of course there will always be punk concerts and hip-hop concerts, but I think that sense of commitment to a lifestyle and a style of dress is gone. You see a lot of elements of style from subcultures that have been assimilated into consumer fashion. If you think about skinheads with boots and skinny jeans, you might see guys like that on any street. If you saw guys like that 20 years ago, you knew he was a skinhead and you were hoping he was a SHARP (Skinhead Against Racial Prejudice). When you saw a dude in a black leather motorcycle jacket, in italian it’s called a ‘chiodo’ and means ‘nail’, only punks were wearing that shit. Now, you go the club and there’s all these chicks wearing them. Then again, it’s the same thing with sneakers and things like that – it all just got spread out. There’s less sense of militance or commitement for urban cultures, even for things like hip-hop and graffiti. I’m just happy that I experienced the pre-internet way to assimilate content and culture.

‘Never Forget The Warriors’ opens at Doomsday Store tonight as part of the Independent Photography Festival, presented with Oakley.

195A Brunswick Street, Fitzroy. 6pm – 9pm.